Original Short Stories

The Night Job

Previously published in Cosmic-Double

“It’s because you’re more Ha’ole than me,” Denton says and I tell him how that’s stupid, because we get the same Mom and Dad. He tells me to think about it but I have thought about it—if Mom is 50% Ha’ole, 50% Chinese, and Dad is mostly Hawaiian with some Filipino, Portuguese, Japanese and Samoan—we’re equally Ha’ole. So I tell him.

“Not even. See, every time Dad and Mom has one baby, it sucks the Hawaiian away from him and the baby becomes more Ha’ole each time. It’s true. Dad was doing pretty good, but when you was born, he lost his roots and he started playing golf. Ditched the tank top for one polo T- shirt. He doesn’t even surf anymore. Me, see, I was born first, I get more Hawaiian in my blood than you, so I look more like Dad, and das why he let me come with him on night jobs and not you. He was too shame for bring you.”

Dad shoots Denton a look so stern, he knows before Dad has to say anything.

“Nah, sorry.” Denton tells me, with fake remorse in his eyes. “I just messing with you. You just never got invited before because Dad only needed one helper those other times. Dis is one bigger job. One restaurant.” He nudges his leg against mine, so I nudge back at him with my whole body. It’s not my fault he slams into the damn door. He deserves it.

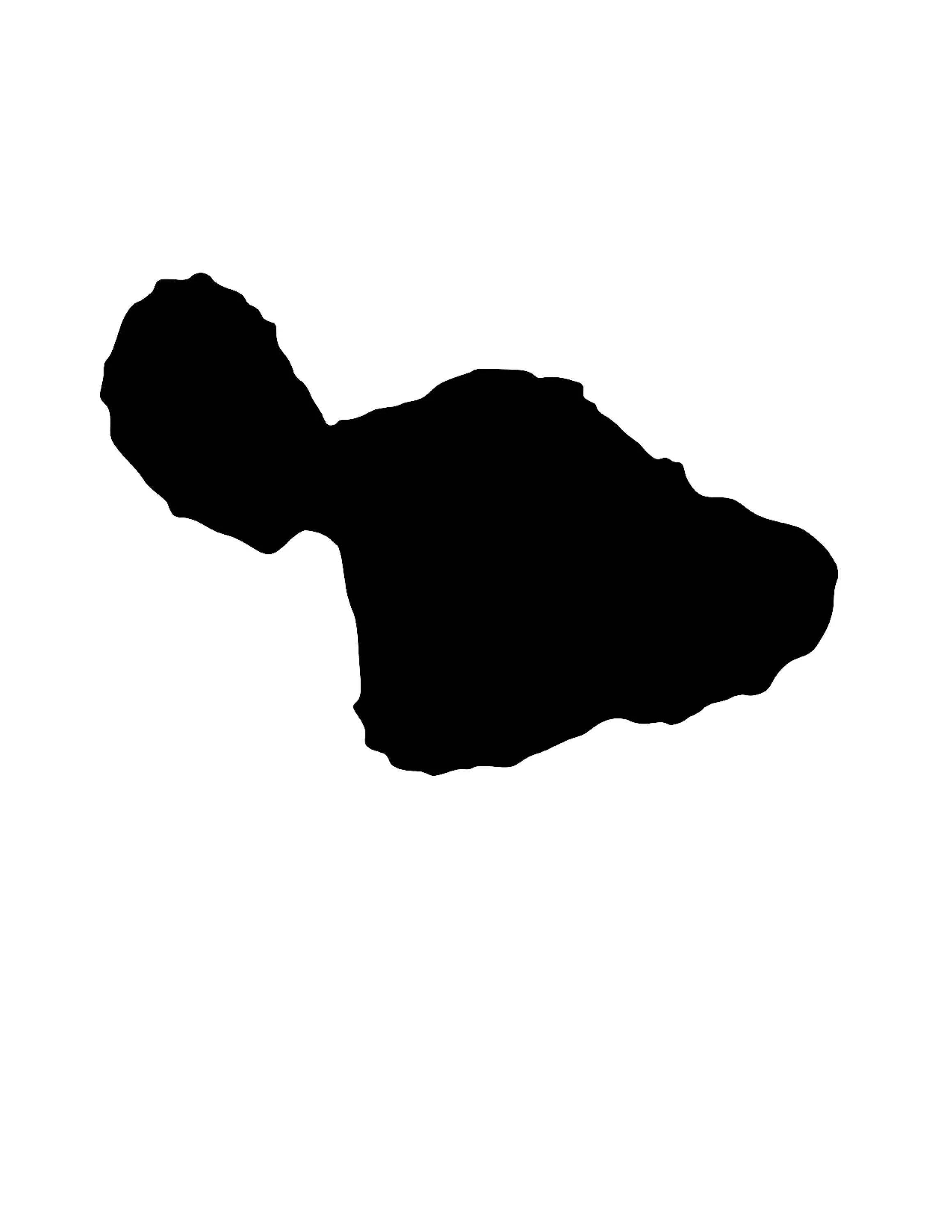

Dad yells at Denton and tells him “don’t antagonize your sister! She’s stronger than you, she could have whacked you right outside the car!”

I laugh but then Dad yells at me too and tells me to share the seat with Denton. I scoot over as much as I can, but on the other side is a toolbox, a metal shaft, and Dad’s carpet cleaning machine. The van only really seats two, but I’m not complaining. I’m looking out the window ahead and thinking about all that sugarcane. Between Kealia pond and Māʻalaea are miles and miles of tall, swaying sugarcane stalks until suddenly there isn’t and then there’s condominiums, the Ocean Center and a great big harbor. All beyond the bend is great Mother Ocean, from the subtle sea-cliffs all the way to Lānaʻi and on to forever. On the mountainside, there’s probably lots of mice, spiders and centipedes crawling in the dirt and grass. I bet there’s even owls, for that matter, out hunting. I ask Dad.

“Pueo? Yeah, I seen them out here plenty of times. They’re spirits half the time so I never like to see them when I drive alone. Especially not in the road. If you evah encounter one pueo in the road, look but don’t get too close. It’s good luck if you see them, but they’re delicate, and killing one is kapu. Just better hope it’s not one spirit!”

We drive through the tunnel and I make a wish with my eyes closed super-tightly. Then all around every turn, over every stretch of dark ocean, every crag in the mountain and along every mile of road, from the Pali trail to Lāhainā, I look out for my pueo. Denton must have used his wish on something stupid, like that Dad takes us to Jack in the Box. Fatso.

9:50pm

From out the back of the van, Dad reels the big grey hose faster than I can keep up with. I watch it pile up on the ground in coils, like a roly poly bug that keeps on getting bigger. It’s pretty much a vacuum hose, and it has ridges, too, like a vacuum. I have to use all of my weight to pull a length of it and straighten it out, then feed it through the railing on the sidewalk, while Denton, up above, runs the hose over to the front door, where he makes another roly poly bug just outside of Bubba Gump’s. Then we do the same thing with the smaller, black hose, the one that brings the soapy water. Dad then takes a couple of bungee cords and calls me and Denton over.

“Anytime you go up a level, or you’re working with stairs, you need to use your bungee cord. Denton, you remember? what I wen’ tell you? How come we do it like dat?” Dad says, but Denton is looking at some blonde lady in a blue dress across the street. He watches her as she comes out of the clothing boutique; he’s still checking her out while she double-checks each lock. Ughhh. Are all boys so obvious!?

Denton turns around quickly when Dad calls his name a second time. “What, Oh!” He says, “Uh, yeah, the cord? You gotta lock up da hose so nobody takes it, ah?”

“Not even,” I say, “You wrap it around the bars and clip it on each side, so the bungee cord keeps the hoses in place. If not, you gotta run back down the stairs, bumbai you gotta go grab the thing again, do all that extra work.”

“Exactly, princess.” Dad says. “Beautiful and smart—how come your braddah can’t pay attention, like you? Denton, stop starring at that lady, yeah, and listen when I talking to you. Only her first time, and already your sistah knows better than you. Come, Chelsey, let the professionals get to work and let googley eyes over there go inside and start putting all the chairs on top the tables.”

“Haaah, googley eyes,” I tell Denton in the most annoying voice I can find. “Go feast your eyes on some chairs. You never know, some ladies probably sat their fat `okole down on top them chairs!”

He sticks his tongue out and makes a sarcastic face at me, with a dumb fake laugh to go with it. Then he opens the door and goes inside the restaurant and I can hear him telling a worker he’s the carpet cleaning guy. He sounds like an infomercial salesman. So mental.

Dad and I go back to the van. In the dark of night, electric blue letters—outlined in chromatic silver—seem to catch any and all passing lights and illuminate the words:

HOAPILI MAGIC CARPET AND UPHOLSTERY CLEANING

Yeah, Dad’s new signs look pretty cool, and I like how there are different numbers for Upcountry and Kahului, even though all the numbers go to Dad’s cell phone. A cell-phone! Pretty killer, right? All those numbers make our family company seem important, like we get tons of locations all over Maui. Whenever Dad gets a call, he pulls the van over to the side of the road and takes out his spiral bound, red leather date-book. He always says, “Hoapili Magic Carpet Cleaning, this is Russell…” and takes down a name, date, time, and address.

Sometimes, Mom takes the calls from her cell phone (yeah, that’s right, she gets to have a cell-phone, too. So unfair!) and then calls Dad or tells him at home. I doubt anybody will be calling us this late though. Everything on Front Street is closed, and the sound of waves crashing against the seawall is probably too loud to even hear a phone ringing, anyway.

Dad slides open the heavy side-door and shows me how to start up the machine. I bet you anything he never showed Denton this, but he knows I’m smart, and I get it right away. Open the red water valve, then if necessary, open up the blue one small-kind, and make sure the orange ball inside the rubber tube doesn’t go higher than the two black lines. Easy. I tell him I can handle it, and he trusts me, so he leaves to go inside. He takes with him some plastic corner protectors and his wand.

The precious wand. It’s the tool he uses, the thing all the hoses connect to. It does all of the cleaning. There’s smaller versions, too, for couches, but the wand is awesome because it’s this huge, titanium steel thing-a-ma-jig, and has a trigger on it that you pull for the hot, soapy water to come out. Whatever the wand goes over, clean carpets come out, whiter even than popcorn ceilings. So it is kind of like a wand, I guess, if you think about it—magic.

I look out for Denton to come give me a thumbs-up, and when he does, I turn on the water and start the machine. The gauge is just where Dad told me to put it, and the machine is roaring super loudly, so I get away just as soon as the job is done. Seriously, the sound is like standing next to propellers of an airplane. I understand why we had to wait until after closing to come clean the restaurant. I follow the hoses up to the entrance. A brave calico cat prances out from behind a dumpster to investigate the source of the monstrous cacophony. If she were mine I’d name her Dotty.

11:25 pm

The bar smells like cigarettes because of the ashtrays, but Dad says its fine for me and Denton to sit there, since he’s almost done anyway. The carpets look really pretty now that they’re clean. You can see big triangles in all of the places that Dad moved the wand, and it creates a damp pattern on the carpet that makes the dry parts look mega-bright.

Bubba Gump’s is just like from out of the movie. There’s pictures of Forrest and Bubba and even Lieutenant Dan, and rope nets full of toy-crabs hang on all the walls. It’s like you’re inside of a fishing boat, only it smells a lot better. On the door to the ladies restroom is a pearl-lined picture of Jenny. I really have to pee, but I’m gonna hold it because I hate her; I hate what she did to Forrest in that movie. Instead I take a seat next to Denton, who appears to somehow have scored a soda from the bartender.

“Oh! Is this your sister?” the spikey haired man says, looking in my direction, and Denton tells him my name. “Howzit, Chelsey? I’m Bryant, but people here call me Matsuda. You like one Dr. Pepper or something?”

“For free?” I tell him and he says of course. “Do you have any Pog?”

“Guaranteed. Anything else? You kids like some fries or something while you wait for your Dad?” He pokes his head around the corner, into the kitchen. “For real, you hungry? I can go tell Jonavan to cook something for you guys, if you like—anything.” He pours some Pog into a glass for me, and puts a tiny-little yellow umbrella on top.

Denton says right on and asks for fries, and I don’t really want anything else so I just tell the bartender, “all your tips, please,” and laugh. I wasn’t being serious but he plops down a water pitcher full of bills and coins.

“For real!?” Me and Denton both say at the same time, while we cup our hands to catch coins before they roll off the table.

“I’ll get your fries,” Matsuda says, “and if you count all the bills for me, you can have all the coins. I’ll be right back.” He flashes a grin and a wink and it occurs to me that he is the best adult I’ve ever met.

Denton scoops half of the money towards himself, and I scoop up the rest. Life is like a game show, right now! There’s 1’s, 5’s, 10’s and even a few 20’s. I’ve never touched all this money at once before. If this guy makes this much money every night, he’s probably rich. I wonder why Dad doesn’t want to be a bartender.

I’m done counting so much faster than Denton, so I start stacking up the coins. The view of shop lights stretching across lava rock, black-blue ocean ripples and a bazillion speckled stars looks pretty sweet over a mound of one-hundred-and-thirty-one-dollars…And seventy-eight cents!

A waitress who looks like a younger version of my aunty Linda—my Dad’s sister—comes over and walks behind the bar. She says hi and asks what we’re doing with all that money.

“Matsuda’s gonna let you have all of his change, huh? But he’s making you work for it? What a cheapskate. Here. I’ll give you each 20 just because I like whatchu did with the carpets. Looks waaaaay better.”

WHAT!? Denton and I receive the gift. We are officially the happiest kids on earth, and Matsuda is now probably unofficially the second best adult I’ve ever met. We separate the coins we get to keep from the bills Matsuda wants to keep. We count up the additional twenties and add it all together…

“Fifty-seven-dollars!” Denton yells.

“And seventy-eight cents!” I remember that we also have the change jar at home, which I keep count of feverishly. “Denton, the change jar! That means we have almost one-hundred dollars!”

We both thank the lady, who tells us to call her Leimomi. Leimomi asks us what we’re gonna buy with our stash. I tell her a pueo, but that jerk Denton tells her no, that we’re going to use it to buy video games.

“A pueo, huh? That’s my family’s aumakua. They watch over my Mom-guys, so I’m gonna hafto watch over them, too, and ask that you don’t try to keep one as a pet. But you can see them sometimes, especially if you drive by the sugarcane. They hunt rats and small critters, but only during the day, not like most owls. Do you know how to spot one?”

“No,” I tell her and I can see that Denton doesn’t either because he’s actually paying attention for once.

“Well, they have round faces, and they’re mostly brown. On the top part of their head, they have these short little ears that look like horns. When they fly, they cruise slow and low. They’re also kind of rare. Most of the time when people think they see a pueo, it’s actually just a barn owl. You can tell it’s a barn owl because the face looks like a big, white heart with two black eyes and a small beak that almost blends in. Pueo eyes are black with yellow, and the face is darker.”

“You know a lot,” I tell her, and I’m truly impressed. I feel ready more than ever to see one.

Then Matsuda comes over with fries for Denton, and starts making trouble to Leimomi, calling her teacher-teacher! He tells us that she throws all her money away at Maui Community College. I don’t see it as a waste, but he says that yes it is because in the end all you get is a piece of paper that says you’re good enough to work, but then nobody gives you a job. I tell Leimomi that I want to go to college too, and she says the world needs more ornithologists. We smile at each other and then she turns away and kicks Matsuda in the butt.

After we pull all the hoses back, and help Dad make teepees with the seat cushions, he gives his invoice to a guy in an office in the back. We’re done. We say goodbye and thank Matsuda and Leimomi, and they thank us too. It feels pretty amazing to be part of a work crew.

“What’s with all the coins, moneybags?” Dad asks me.

“The aunty and uncle at the bar let us have some of their tips.” Because it’s me saying it and not Denton, Dad doesn’t ask any more questions.

“Huh,” he says, and opens the driver’s side door. He grabs a white towel and wipes down his face. Something is happening. There’s like a real positive vibe going on. If we were going home, he would have been inside the car already, but he’s not, he’s just looking at us. This may be one of Dad’s rare moments he wants to spend money.

“Wanna go see a movie? There’s a midnight showing.” He says and I was right!

“Yes! Dad, you the man, Dad. Can we see Chill Factor? I heard that movie was sick!” Denton says. He bounces around, and his face is covered by stray, dark curls.

“Is that the one with Cuba Gooding Jr.? Action movie, yeah? Shootz, we go. As long as you’re paying.” Dad says but there is no way in a million years that he’d make us pay.

1:42 am

We exit out the back of the theater, and I’m surprised to find that it’s colder outside than Haleakalā at sunrise. My hands are sticky from skittles and my legs are covered in chicken skin. Front Street looks like a prop-town in a forgotten playhouse. It’s so quiet, even the street lamps are sleeping. Dad and Denton are yelling lines from the movie at each other and fake-driving away from make-believe explosions all the way back to the van. I follow behind with my eyes half-shut. Ha! It’s kinda fun to just follow the sounds, and try to walk just by feeling.

“SHET!”

Dad and Denton come running back to me. “What, what!? What when happen, honeygirl?” Dad says with one hand resting to embrace my shoulder and the other on my hurt leg.

“The sprinkler. I, I hit the damn sprinkler!” I manage to yell.

“Can you walk?”

“…Yeah?” I answer. Like, sure, I can walk but I hit my damn shin, it really hurts. I’m tired!

Denton gets in my face real close like he’s analyzing me. His breath smells like mochi crunch and rubbish. “Dad,” he says, looking back, “this dummy was sleepwalking and trying for carry on like nothing!”

I hate how Denton just knows everything, yet he gives me zero credit for walking as far as I did. He doesn’t bother to tell Dad anything about me avoiding the wet grass and benches or any of that. Dad looks at us both and tells Denton to carry me.

“What!? Dad, Chelsey’s one big girl!”

“Carry your sister. She’s only nine.”

“I’m only thirteen! Dad, she’s like, super tall. I cannot carry her. Plus, she’s fine, look!”

“I agree,” Dad says. “You ARE too small for carry your sister!”

Denton scoffs and tells me get on his back. There’s no way I’m letting him carry me, but there’s also no way I’m going to miss a chance to watch him fail at something. I jump onto his shoulders with extra jump so that he’ll stumble, but actually I land without really any impact. Whatever. At least I can just cruise while Denton does all the walking.

The waves look so pretty this late. I can’t believe they slam so close up the seawall, this near to the road and all of the shops. I wanna see one so big, the white wash splashes onto the sidewalk, like, all foamy, and Dad gets barreled just standing there! I bet Bubba Gump’s is gonna have to move up the street one day, so they don’t get flooded by high-tide.

Denton puts me down by the van.

“Hey, thanks…” I tell him.

“Pshhh, easy! I could have carried you even farther, too, if I wanted.” He gets in the van first, so this ride, I’m the one who only gets to have one cheek on the seat. It’s better though, because I can dangle my sore shin off to the side.

The way back feels like it’s faster. In barely five minutes we’re already by Launiupoko. It’s dark, but you can see the fishing lines cast out into the water, with their hanging lanterns and the occasional head-light of a patient fisherman. Campers.

Now, Denton is getting pretty caught-up trying to convince me that Dad’s van could be used to transport a deadly chemical weapon, like the one called Elvis in the movie. He’s so dumb when he’s pumped up on action movies, like anything is possible even without any skill or preparation. I remind him how, like, in the movie, the two guys had an ice-cream truck, and that was perfect, because they could keep Elvis at a proper temperature, and it would never blow up as long as it stays cold. Dad’s van gets super-hot.

“Yeah, but like,” he says, pausing to catch the right thought, “Dad transports tons of other deadly chemicals. Every day. All that detergent and those special cleaning fluids? You think you could drink those and live? No way. Probably choke flammable, too—you light one match, boom! The whole thing goin’ blow up.”

“That’s pretty cool, actually.” I say, feeling the wind chop through my coasting fingertips. My mind drifts away on an inviting air-current.

My Dad drives around every day, and without thinking about it, he’s out there living like an action star, driving around with powders and sprays that could detonate or like, poison the bad guys. That’s a pretty good movie, right!? He’s a Carpet cleaner as much as the public can see, but really he’s a secret agent who works with chemical explosives to take down actual criminals. That’s so cool. I bet that movie can take us to the top of the box office.

It’s such a rad night, I’m thinking. First we get to go work and make money, then we get to see a movie at midnight, then we come up with our own million dollar blockbuster. I look over at Dad, driving, and he’s even more alert than the two of us. It’s probably because he’s ready for anything. He’s used to the danger already.

Denton and I turn our attention back on the tips we made. If it’s a couple of video games he wants, I’m actually pretty much fine with that because that’s what the change jar at home is for: Captain Commando on snes. Forget sega, and Dad won’t let us have an N64 until it gets cheaper. Anyway, we still get enough money for another game! I’m for sure using mine’s for Final Fantasy III. Denton tells me no right away, and says we’re getting a fighting game. That’s so stupid! We already have Killer Instinct and that’s plenty. He won’t even listen to me, all he wants to know is which fighting game we should get.

“None, of them!” I yell at him. “Mortal Kombat III gets old in two days every time we rent it, same with Primal Rage, same with the Ninja Turtle one. If not Final Fantasy we should at least get something that lasts longer, like Donkey Kong Country 2 or 3. As long as Monster Mega has those games, there’s no way I’m gonna waste money on your dumb game.”

“Oh wow!” Denton laughs. “Donkey Kong is seriously the dumbest, little kid game. You have the worst taste in video games.”

“Shaddup already! I do not. I just like games with some adventure and a little bit of a story. Plus you already got to choose Captain Commando!”

“You agreed we should get Captain Commando! Plus, it has plenty adventure! And we can play together, not like some dumb fantasy game where I watch you play for hours and I just sit there with one useless controller in my hand. Unreal, you selfish brat!”

I cannot believe I’m the one being called a selfish brat, when he gets to pick everything. There’s no way I’m not pulling his hair right now, so I grab a fluffy handful. It’s like grabbing a bunch of oily curly fries, except the curly fries are attached to a crying wussy. Everywhere my hand goes, his head goes, like he’s my puppet, only this puppet makes noise without me having to move my lips.

“KNOCK IT OFF!” Dad yells, and I look at him, but while he’s looking at me and Denton, I’m looking at the road now and I really wish Dad would look too because there’s something in the road—something in front of us—gold, with shiny white tips–

“OH MY GOD IT’S A PUEO! DADDY! THE ROAD!” I scream right at the very moment it becomes too late.

2:12 am

Feathers are everywhere. No one ever told me owls turn into feather bombs in self-defense, not even Leimomi knew that. I’m sneezing, I’m crying, little feathers keep getting in my nose and now I’m sneezing some more. My ears are ringing. This is so bad! Dad’s outside on the phone with Mom. He’s talking frantically, and Denton is out searching down the side of the road for the bird. I really hope she’s fine and she just flew away. I don’t want Denton to find her. Please, God, don’t let Denton find her.

Dad’s yelling on the phone, telling Mom that he was watching the road. I hear him say that he did read the signs on the road.

Yeah, I know it’s one hundred dollah fine.

No, we going make the damn kids pay.

“They have money. Yes, they have their own money. They got tips from the waiter.”

Oh no! I think. I mean, I feel like the meanest person in the whole wide world—my Dad killed a pueo!—but now he’s going to take our money, like we killed her? Now my tears are, like, gushing! I look through the blurry cascade and into the night and see there’s nobody around. No witnesses. No cars. No poles out. We’re past Oluwalu and there’s nothing but kiawe, coral, and sand. Still, God knows that we ran over a pueo. What am I going to tell Leimomi? I didn’t mean to hit your ancestor, Leimomi, I’m so sorry! Nooooo! I can’t take it. I go just past the road so I can curl up in a ball over by the pebbly shoreline. I. Can’t. Stop. Cryyy-iii-ng.

“Dad!” Denton yells from far off. Dad waves him away, and turns around to talk more on the cell phone. So Denton yells to me. “Chelsey! Chels!” I hear his wet slippahs flip-flopping through the empty night until he’s right next to me.

“Hey,” he says, out of breath, but smiling.

“Yeah?”

“Look,” he says, and I uncover my head from my balled-up knees to see.

“Oh my gosh!” I scream, and curl back into my ball.

“Yeah! See. Look!” he says, with a dead owl stretched in-hand from wingtip to wingtip. “It has a white face. Look. White face…? Looks like one heart?”

I don’t understand and I just want him to get away before we get even more cursed. I have never seen something that dead before. How come nobody tells you an animal looks so alive when it’s dead?

I peek my head out to talk to him. “Yeah, so it’s white. Okay? Well we killed it and now we’re cursed!”

“Dummy, don’t you see? It’s not daytime! Even still, here she was, out hunting. Nobody’s getting cursed. We get to keep our game money! And we’re not gonna get fined either!” He turns to Dad, who gets it before I do. Dad says bye to Mom and ends the call.

Dad walks in a small circle, looking around for us. Then he sees us and walks over.

“You okay?” He crouches down and takes a look at Denton’s dead owl. He looks long and hard into the bird’s face, like he’s trying to determine if he recognizes her from around the neighborhood.

“Oh shet!” Dad finally lets out. “It is just one barn owl. Pshhh, no worries! Kids, put that down. Just one barn owl! Buggah is invasive, anyway. Hahaha! Shootz; kids, get in the van. Let’s go home. Your Maddah stay worried. ”

So we do.

The boys step away from the bird to let it keep on dying however it’s supposed to. I leave my slippahs behind accidentally-on-purpose so I can tell them I have to go back for them. Really I just want to take one last look at her, to see her scared yellow eyes, and to remember all that she was. She was invasive, but she was beautiful. She was probably a mom. Up until we came, she was flying; just a minute ago! She was alive, but now she’s not.

She was.

She was.

She was.